Posted by The Villager on June 20, 2013

Remembering George L. White By Nicholas Pircio

Friend of Slaves

The Underground Railroad flourished in Cattaraugus County during the years leading up to the Civil War. Railroad routes crisscrossed the county as slaves made their way north toward the Canadian border and freedom. One of the railroad stations happened to be located in the hamlet of Cadiz, just west of Franklinville.

The Ischua Valley Historical Society has recently been focusing on Cadiz, which celebrated its bicentennial, and the life of George L. White. A sign was unveiled in front of the Howe Prescott Pioneer House, detailing the history of Cadiz, thanks to a generous gift from the James Bush estate. Historian Maggie Fredrickson, Curator of the Miner’s Cabin Museum and the Howe Prescott House, says a number of abolitionists lived in Cadiz. One of them was William White, who was deeply religious. His son, George L. White, grew up in Cadiz.

Fredrickson says William White was a very unusual man. “He was somewhere between six foot five and six foot seven, which for that time of history was a very big man, bigger than Lincoln. His son George most probably saw the activity with the slaves and probably heard the slaves singing the Negro spirituals. Both he and his father were musically talented.”

After George grew up in Cadiz, he went on to Ohio, where he became a school teacher. He was teaching children who were freed slaves. “He ended up in the Ohio 73rd and fought at Chancellorsville, Gettysburg and Lookout Mountain in Georgia, where he became seriously ill.” Fredrickson notes that although no longer able to be a soldier, George L. White stayed with the regiment as bandmaster, because of his musical talent.

Once the Civil War ended, White became involved with a school in Nashville that took in freed slaves, to teach them reading and writing. Fisk University, which still exists today, hired White as their treasurer. He also taught music there. “He became very enamored of the Black spirituals such as ‘Swing Low Sweet Chariot’ which were never recorded. That’s because they were almost like prayer and very private. But, they (the slaves) got to trust in him and taught him these songs.” White managed to transcribe many of the songs, which might otherwise have been lost.

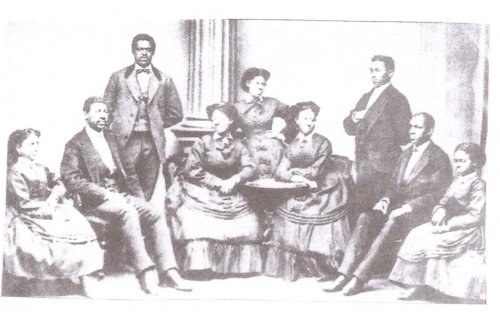

As a result, White formed a choir and called them the Jubilee Singers, composed entirely of freed slaves. “He started to put on concerts and tried to raise money for scholarships for freed slaves,” seeing as Fisk University started as an old Union Army hospital and was falling apart. He travelled around the country with the singers, who had a tough time of it. “They weren’t allowed to sleep in regular hotels. In one place they had to sleep in a woodshed. They were very poorly clothed and some restaurants wouldn’t allow them in, and some churches wouldn’t let them come in and sing.”

But eventually, the jubilee Singers became so well known that doors started opening up to them. “They did several tours of Europe for kings and queens and so forth. In the long run, he (White) raised over $150,000. Today that would be equivalent to $2-1/2 million. That’s in addition to preserving the music.”

White retired to Fredonia and later to Elmira. But he had no money. Fredrickson says, “He often used his own money to sponsor the trips and went through his savings. When he was an invalid, his wife had to go to work to support them and had to take a job as a housekeeper. His goal in life was to always to keep Black women from just being housekeepers. He wanted them to have an opportunity to be teachers and to go into other walks of life. And yet, that’s how they ended up.” White died at age 58 of a massive stroke and is buried in Fredonia. “But he had an incredible life and an incredible effect on music. Hundreds of songs are available today that probably would (otherwise) have been lost.”

Source: Reference onlt to Ischua Valley Historical Society